The COVID-19 disruption has forced organisations worldwide to embrace remote work. Tech giants such as Twitter, Facebook, and Shopify all announced that their employees would have the option to work from home permanently. Furthermore, even some companies in industries with more conservative work cultures have also allowed permanent remote working, as in the case of Nationwide Insurance in the United States. Remote work is nothing new, and research has shown that employees that work remotely experienced increased productivity, better job satisfaction, fewer intentions of quitting, and were able to enjoy a good work-life balance (Gajendran and Harrison, 2007).

However, this same review found that these benefits begin to tail off after 15 hours of working remotely. One reason for these diminishing returns may well be the stress of work-enabling technologies, such as Microsoft Teams, Zoom, and other project management applications. We refer to the stress of having to adapt to changes in the use of technology as Technostress.

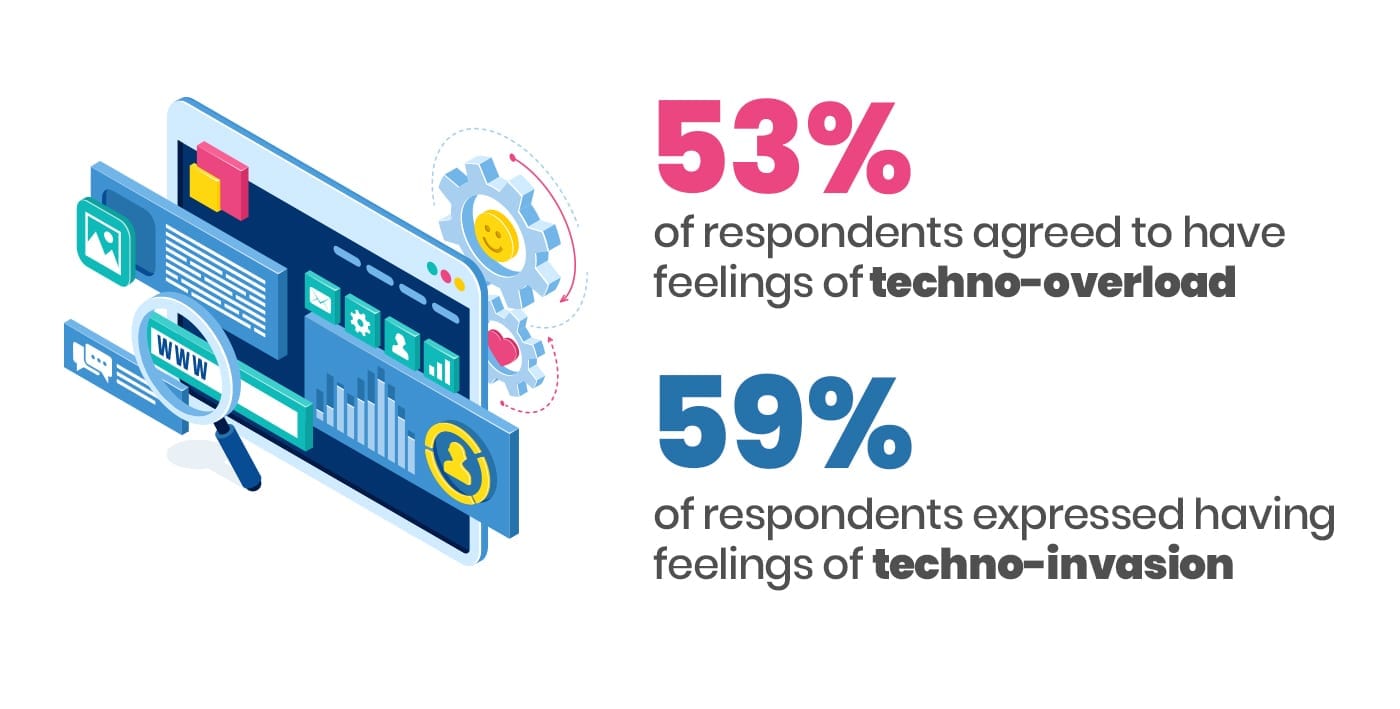

Tarafdar et al. (2007) suggested that technostress could be brought about in several ways; however, we concentrate specifically on techno-overload and techno-invasion. Techno-overload is the feeling of having an increased workload when working remotely due to the use of work-enabling technology. Moreover, Techno-invasion is the feeling of being pressured to be responsive to work demands at all times, and a sense of having one’s personal or family life invaded by the use of work-enabling technology.

As many employees may likely continue to spend a significant amount of time working remotely, organisations and managers will find value in understanding factors that influence employees’ technostress, and more importantly, ways of alleviating this stress.

To get some insight into employees’ technostress during COVID-19, we conducted a study involving 242 participants working across various industries, including banking, energy, education, and the public sector. Our key hypotheses were centred around organisational and personality factors that could influence technostress, and ultimately the consequences of technostress on employee engagement. Specifically, we wanted to shed some light on three big questions, as expanded below:

HYPOTHESES

1. What factors increase or reduce technostress?

We hypothesised that organisations’ reshaping capabilities – that is, their readiness for employees to work remotely – would increase employees’ technostress. It may seem a bit of an irony that this readiness would increase technostress. However, we suspect that as organisations made the necessary preparations to ensure productivity continued during remote work. They may have perhaps inadvertently, created performance expectations that prompt employees to work longer and disrupt their personal lives, as they try to come to grips with new technology and work structures.

We also hypothesised that employees that have a good supportive relationship with their managers would experience less technostress. We believed that employees with supportive and trusting managers that allowed them some autonomy would be able to handle the change in work structure and use of technological tools better.

Although the organisation may have laid down a standard plan and expectations of how work should be done, employees that leverage the support and trust of their managers can through discussion, devise creative ways of dealing with the transition to remote work.

2. How do employees cope with technostress?

Technostress sounds like it is inherently harmful – a disruptive force in our work lives. However, this is not necessarily the case. While some people buckle under a level of stress, others might thrive under similar levels of stress. We have learnt from transactional stress theory that some employees will view technostress as a challenging stressor and will rise to confront the stressors head-on, while others will see it as an obstacle, and will seek to avoid the source of their stress.

In our research, we hypothesised that employees that view technostress as a challenge would proactively seek feedback from their colleagues and managers – that is, ask questions to aid problem-solving. Moreover, employees that view technostress as an obstacle stressor will engage in destructive voice – that is, bad-mouth their employers and blame them for the stress they are experiencing, instead of dealing with it. This latter coping strategy (Obstacle stressor) could be a way of deflecting blame for being unable to come to grips with new technology and digital work structures.

The first type of employee has a learning orientation and focuses on improving their task competence. The second type of employee has an avoidance orientation, seeks to avoid looking incompetent, and is more concerned with impression management than task competency.

We believe that learning-oriented employees will engage more in seeking feedback from their colleagues and manager. In contrast, avoidance-oriented employees will more intensely turn to destructive voice behaviour, bad-mouthing the organisation as a way to handle technostress.

3. What are the effects of technostress on employee engagement and attitudes towards future remote work?

Keeping employees engaged at work is a recurrent issue for managers and organisations and has become even more pertinent with remote work during COVID. With less frequent face-to-face interaction, managers may not be able to get a good read on employees’ attitudes and commitment to their tasks. We believed that technostress would affect employees’ level of engagement, depending on which coping strategy they chose. We expected that employees that dealt with technostress by seeking feedback from colleagues and managers would end up being more engaged at work. Frequent feedback-seeking implies frequent communication between team members, and can help to reduce feelings of isolation, create a sense of belonging, and fuel engagement. However, we predicted that employees who used destructive voice to air out their frustrations would be less engaged, as this may be a symptom of fatigue and dissatisfaction with remote work.

Just as we hypothesised that organisations’ reshaping capabilities and a supportive manager-employee relationship would affect employees’ technostress, we also believed that these two factors, based on the employee’s coping strategy, would also influence the employee’s job engagement.

Although we expected that organisations’ reshaping capabilities would increase employee’s technostress, we assumed that it would also have some positive effects, such as capacity development through upskilling in digital skills and increased job engagement. We thought that this same readiness to prepare employees for remote work would also provide better reporting and communication structures for employees to seek, hence facilitating better job engagement.

Regarding the future of remote work, we believed that employees that were well-engaged working remotely during the COVID confinement period would be willing to continue that arrangement even after employees are allowed to return to their workplaces en-masse.

As we have shown, there are many unknowns regarding employees’ attitudes to remote work, and there is a lot we must learn. However, many organisations have already welcomed back their staff to workplaces, yet in a reduced capacity. The world is still far from being back to ‘normal’. As organisations rethink their work structures, we provide some guidance by giving answers to the crucial questions we have explored.

FINDINGS

Organisations’ reshaping capabilities increase employees’ technostress.

For employees to transition harmoniously to remote work, organisations must have reshaping capabilities – that is, a well-structured roadmap involving the deployment of new technology – and communicate to employees how this change fits in with organisational objectives. Some encouraging news is that 71% of respondents in our study, agreed that their organisations were well-prepared for them to work from home, but there is a lot of headroom for improvement. The not-so-great news is that organisations’ reshaping capabilities significantly contributes to employee technostress.

This finding was further supported when respondents were asked to rate the effectiveness of their home technology infrastructure (Wi-Fi, computer, power supply) in enhancing remote work, and the average response was about 67% effective – again, much room for improvement. These statistics show a slight discrepancy between the employee’s perception of the readiness of their organisation for remote work, and the employee’s own ability to work effectively at home, bringing about technostress.

The majority of employees we surveyed are indeed experiencing technostress. 53% of respondents agreed to have feelings of techno-overload. That is, work-enabling technology was increasing their workload, forcing them to work within tight time schedules, and forcing a change in their work habits. Even worse, 59% of respondents expressed having feelings of techno-invasion, where work-enabling technology has disrupted personal and family life and forced employees to work past official working hours. Feelings of technostress were indeed prevalent amongst our respondents, despite 76% of them claiming to be receptive to new work-based technologies, and in fact, being first adopters of such technologies.

In the case of transitioning to remote work during COVID, one would think that organisations with well-structured business continuity plans that cater to remote work should not increase employees’ technostress. However, just because the company is prepared does not necessarily mean that the employees are prepared as well. Most large technological changes in organisations are discussed and implemented top-down, such that while a plan is brilliant on paper, it may overlook the feasibility of such plans for many employees. In defence of leadership, especially in larger organisations, it is challenging to come up with a ‘one size fits all’ plan for all employees.

Often, when organisations’ leadership roll out their plan for technological change, there may be an expectation that employees can continue to fulfil their tasks as expected. However, employees may need time to adjust to these changes. They may find themselves working longer than usual and sacrificing personal time to get up to speed with new technological tools and the newly established working structure. We recommend to organisations in developing new processes or systems, to prioritise employee inclusion during the development phase. For instance, Leaders should include employee representatives as part of development teams. These employee representatives will not only bring employee considerations into decision making. They will also serve as change agents to facilitate the assimilation period for their colleagues.

It is also essential to communicate the changes being introduced along with support available, such as training, to help employees adjust to the changes as fast as possible. Organisations should ultimately be aware that there should be an adjustment period for changes in work structure and should account for this in their planned changes.

Employees must also take responsibility for their development of new skills required for business continuity and the digital age, taking advantage of all support provided for development. Upskilling and development are primarily the responsibility of the employee to remain competitive in our ever-changing business climate. This proactive self-development would support career aspirations and growth.

A supportive relationship between managers and their employees reduces technostress.

Employees that reported having supportive relationships with their managers indicated having significantly lower levels of technostress. Organisations should be prepared to pivot and implement work structures that allow the business to continue in times of crisis. It includes clarifying the organisation’s expectation to managers on their role as “employee support providers”. Often, especially for larger organisations, it may be impractical for the leadership to consult with all their employees before making decisions. Hence, it is essential to keep team managers in the loop so they can explain any changes in work structure, as well as the organisation’s expectations regarding employees’ productivity.

Team managers should discuss with their team members either as a group or individually when appropriate. It is during such one-on-one discussions that team managers can elicit any challenges employees are facing, such as connectivity issues at home or difficulty learning how to use new technological tools. These challenges are more likely to be worked out when the employee enjoys a good supportive relationship with their manager. The employee can freely air their frustrations, and better understand what the organisation’s performance expectations are. For employees with excellent relationships with their managers, they may be able to negotiate flexible work arrangements such as different working hours and goal settings, depending on caring responsibilities. These manager-employee discussions can result in creative ways to meet performance expectations without getting overwhelmed with the demands of being connected to work at home.

72% of the respondents stated that they enjoyed a supportive manager-employee relationship. It might seem like an encouraging number; however, does this mean that employees who have a somewhat complicated relationship with their manager may find that they are unable to cope with technological change and performance expectations as they work remotely?

The role of a “manager” is a multi-faceted one, where managers must play multiple functions such as coach, supporter, appraiser, technical and behavioural advisor. Furthermore, staff managers must possess not only technical competence to deliver on the job, but also the emotional intelligence to lead their teams to successful delivery. It is the responsibility of managers to study their subordinates, interpret their behaviour and manage each employee as required. Identifying those who appear more disconnected (i.e., not performing optimally or disengaged from the rest of the team) and deploying engagement strategies to ensure the employee remains connected to the team goals.

It is crucial during the hiring or promotion process to test the emotional capability of an individual to act in the capacity of a manager and how they deal with high pressured environments, to ensure the right managers are placed in teams. One of the ways to do this is conducting psychometric assessments as part of the hiring process to reveal the emotional intelligence capacity and work behaviours of candidates.

pcl. offers the accredited Thomas International Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue) to meet this need. TEIQue is an emotional intelligence assessment designed to tell you how well staff managers understand and manage their emotions, how well they interpret and deal with the feelings of others and how they use this knowledge to manage relationships.

As part of organisations’ roadmaps to ensure a seamless transition to remote work, managers should be adequately trained on how to communicate effectively and cultivate supportive one-on-one relationships with all their team members, most especially the more disconnected employees. Some of the ways to reduce the effects of technostress, include r communication and check-ins between managers and employees to discuss how they are settling in with new ways of working. This can be accompanied by structured feedback sessions such as Stay Interviews. During stay interviews, managers discuss and proffer solutions that will encourage their subordinate to continue working for the organisation. This can help to promote trust in managers and the organisation and also help to reduce technostress.

Managing employee behaviours in response to dealing with Technostress

Employees that view technostress as a challenge will cope by seeking feedback from their manager and colleagues, which is excellent because this leads to higher levels of job engagement. Our findings also confirmed that although the level of an organisations’ readiness to transition to remote work, increased employees’ reported levels of technostress. The same eagerness also provided a virtual work environment, which allowed employees to seek feedback from peers and their manager in real-time. It brought about an increase in employee engagement.

Once more, technostress is not inherently harmful. As mentioned earlier, some individuals thrive when faced with a challenge, while others can have their productivity significantly reduced by the same stressors. Although most employees will be consistent in the coping strategy they choose to deal with technostress, these strategies are – about 57% of employees used both coping strategies. However, 83% of employees firmly agreed that they sought frequent feedback from their colleagues and manager during remote work. In comparison, 21% agreed to bad-mouthing, being overly critical, and insulting their organisations’ work from home policy. Managers must understand the two types of employees and how they cope with technostress. One method is to conduct personality profile assessments during the recruitment process or when forming a new team.

Personality profile assessments is a behavioural test that provides accurate and non–critical insight into how people behave at work. Based on employee results and insights, managers can deploy different management strategies that would positively impact employee behaviour.

We initially believed that feedback-seeking behaviour would be accentuated in individuals that were more learning-oriented – that is, people eager to develop their competence. We thought that technostress would present new puzzles that learning-oriented individuals would be keen to solve, through more frequent consultation with colleagues and managers. One explanation for this might be that learning-oriented individuals tend to be more autonomous, and can figure things out for themselves, mostly when they work in isolation from their team.

Overall, we found that employees who regularly seek feedback on their work from their peers and managers were more likely to be engaged in their jobs. Managers should schedule regular private check-ups with members of the team to ensure employees are coping well with the new work set-up. Even high potential, learning-oriented employees must be regularly checked on by their managers, as they might be silent about challenges that could be revealed during check-in sessions. Seeking frequent feedback from work teams may not come naturally to all employees, so managers should provide ample opportunity for sharing sessions, as well as encourage employees to seek the necessary feedback privately when necessary.

Employees who view technostress as a hindrance will cope by engaging in destructive voice, i.e., bad-mouthing the company. Individuals that have more of a performance-avoid orientation- that is, individuals that shy away from taking on tasks for fear of seeming incompetent to others – had a significantly higher likelihood of using destructive voice to cope with technostress. This coping strategy is used to avoid appearing incompetent and to deflect possible blame for deficiencies in productivity, given the challenges of remote work.

Our findings did not reveal a significant negative relationship between employees’ destructive voice and job engagement as we predicted. Nevertheless, frequently bad-mouthing the organisation is ultimately bad for staff morale and detrimental to the organisation’s image.

Interestingly, we did find that employees that had a supportive manager-employee relationship, despite using destructive voice as a coping strategy, were four times more likely to be engaged than employees without this supportive relationship. This result is perhaps because such employees can confide in their managers and voice their frustrations more freely, which may ultimately lead to collaborative solutions to the challenges of working remotely. Hence, managers must build strong relationships with their employees, centred on trust and open communication, such that employees are free to express their thoughts.

This creates a safe space where employees can vent, and managers as spokespeople for management can clarify, and inspire a positive change in employee behaviour, aligned to achieving organisational goals.

Prepare for more flexible work arrangements in the future.

Survey respondents who reported to be engaged in their jobs during lockdown were more likely to be willing to continue working from home post-lockdown. More importantly, we discovered that prior remote working experience was 4.5 times stronger than job engagement in influencing employees’ willingness to continue working from home.

Our analysis also revealed that the availability of adequate home technology infrastructure was three times stronger than job engagement in influencing employees’ willingness to continue working from home. Now that everyone has had a taste of remote work and had time to adjust to new ways of working, they should be more comfortable making remote work a more regular part of their routine. On average, our respondents spent 31% of their time working from home pre-COVID.

We may now begin to see more employees negotiating more flexible working arrangements with their employers, as 62% of our respondents agreed that they were willing to continue working from home post-confinement. Organisations that allow this flexibility may ultimately have the upper hand in attracting the best talent.

Summarily, organisations and managers have a role to play in managing employees’ technostress in their remote work environment, especially given the potentially negative impact of technostress on some employees’ job engagement. Organisations must prioritise employee representation in decision making, with a well-rounded approach, clarifying roles and ensuring appropriate support to accommodate and shorten the adjustment period. Both organisations and managers need to keep an eye on employee engagement levels. They should do as much as possible to increase it by ensuring they have the proper digital communication channels in place, as well as, scheduling regular catchups to understand how individual employees are coping with remote work.

These actions can provide the organisation with useful information that can be used to improve work structures and become more resilient to possible future disruptions, which prevent employees from being physically present at places of work. It is likely that after this experience, most employees will want some flexibility in their working arrangements. Organisations and managers must be ready for this shift in preferences, as it is likely to be a critical decision in whether employees stay with their current employer or find another one that offers this flexibility.

Written by:

|

| Dr. Reika Igarashi |

Dr. Reika Igarashi is a postdoctoral research fellow in Marketing at Leeds University Business School, the University of Leeds in the U.K. with interests in work engagement, technology-related stress, and burnout in workplaces.

|

| James Adeniji |

James Adeniji has a PhD in Marketing from the University of Leeds, and is currently a retail analyst at The Very Group. His research interests range across contemporary marketing issues including salespeople’s proactive behaviours, and has published case studies and articles in strategic management.

|

| Nimi Adeyemi |

Assistant Consultant (pcl.)

References:

Gajendran, R.S. and Harrison, D.A., 2007. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of applied psychology, 92(6), p.1524.

Tarafdar, M., Tu, Q., Ragu-Nathan, B.S. and Ragu-Nathan, T.S., 2007. The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. Journal of management information systems, 24(1), pp.301-328.